Preparing for the Coming Wave of EU Sustainability Regulations

EU regulations are causing a paradigm shift in the development of sustainable finance worldwide – firms should prepare to navigate it.

Since signing the Paris Agreement on climate change in 2015, the EU has been pushing an ambitious package of sustainability regulations. These measures broadly press financial services firms to explain and disclose how they consider sustainability in their investment processes. The most recent, the upcoming Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, will require companies to conduct human rights and environmental due diligence across their own operations as well as their supply and value chains.

For funds, asset managers and corporates who do not meet the required standards, these measures raise the real risk that they may be blacklisted by larger institutional investors looking for partners who can meet their responsible investing goals. They also pose significant compliance challenges, as companies strive to understand these evolving obligations and collect the right data for sustainability disclosures.

Evolving EU regulations

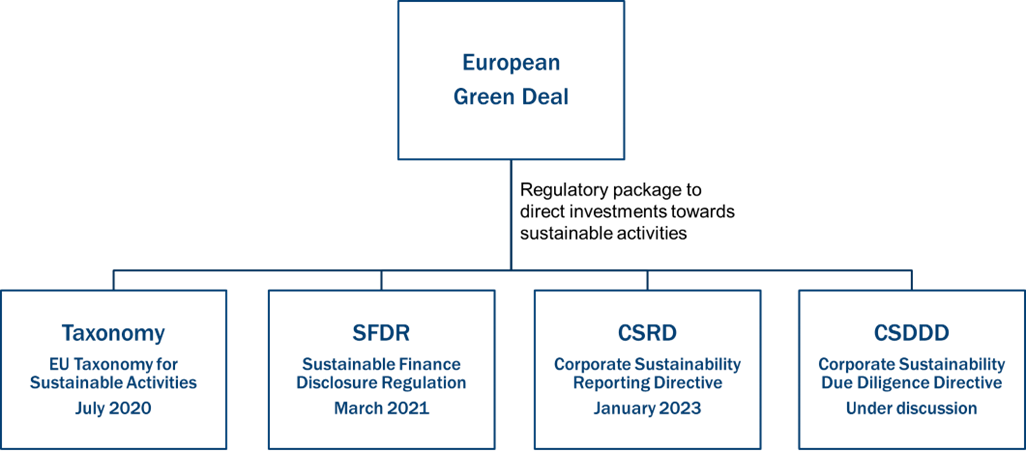

The recent package of sustainability-focused regulations forms a key pillar of the European Green Deal, a set of policy initiatives with the overarching aim of making the EU climate neutral by 2050.

The EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities is the rulebook defining which economic activities can be classified as environmentally sustainable. The Taxonomy lays the groundwork for the other sustainability regulations outlined below and establishes mandatory disclosures that companies have to publish under other regulations. For example, under the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR, see below), asset managers must declare which proportion of their sustainable investments is Taxonomy-aligned.

SFDR mandates that asset managers marketing their funds as sustainable must make disclosures to substantiate their claims. Under SFDR, asset managers are required to classify their funds as either non-sustainable (Article 6); promoting ESG characteristics (Article 8); or sustainable (Article 9).

From 2024 onwards, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) will require companies in scope – around 50,000 large public-interest companies, including listed companies, banks and insurers – to annually publish a wide range of ESG information. The regulation requires they conduct a “double materiality assessment”, meaning that they should identify and mitigate both ESG risks affecting the company as well as the company’s impacts on people and the environment, among other requirements.

The aforementioned Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) is an upcoming regulation which will require companies to conduct human rights and environmental due diligence in their own operations and their supply and value chains. The regulation asks companies to identify, bring to an end, prevent, mitigate and account for negative human rights and environmental impacts. It also introduces duties for directors, including setting up and overseeing the implementation of the due diligence processes and integrating due diligence into the corporate strategy.

Though these regulations differ in scope, they have two key characteristics in common. Firstly, they ask investors and corporates to explain and improve their governance of ESG risks and opportunities. This requires entities in scope to review their due diligence and risk management systems to incorporate these requirements. Secondly, the regulations require corporates and investors to publicly disclose extensive ESG information with the aim of redirecting financial flows towards sustainable activities and, at the same time, curb greenwashing.

A regulatory revolution

These rapidly evolving sustainability regulations are part of a paradigm shift on sustainability and ESG in Europe and beyond its borders. Investors are feeling pressure from their limited partners: many – particularly major institutional investors like pension funds, insurance and sovereign wealth – have to comply with these regulations themselves, or are pursuing responsible investing standards that set strict ESG criteria for their potential investees. LPs are also increasingly wary of reputational damage from investing in funds and corporates which mis-represent themselves as sustainable or pro-ESG under SFDR. Corporates are similarly feeling the pressure from their consumers. All parties have an eye on potential regulatory enforcement.

For those who doubt the potential impact of Europe’s ESG and sustainability endeavours, consider the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). When GDPR came into force in 2018, some industry commentators expressed scepticism over its reach and enforceability, arguing that the law would only produce small changes in companies’ approach to privacy. However, GDPR has become the gold standard for privacy not just in the EU but worldwide, prompting companies to change their strategy, policies and processes on this topic. National regulators in the EU have pursued enforcement, imposing increasingly significant penalties for GDPR breaches.

Additionally, Brussels’ ESG-focused regulatory efforts will not only affect EU-domiciled companies. Like GDPR, they will have an extra-territorial impact. Most notably, certain sustainability regulations directly apply to non-EU companies if they operate in the area, including SFDR disclosure requirements for those selling financial products. Similarly, ESG reporting requirements under CSRD apply to non-EU companies which generate a net turnover of more than EUR 150 million in the EU and have at least one subsidiary or branch in the union.

How to surf the ESG wave

It will be paramount for corporations and investors to adopt a holistic approach to ESG. Players who will attempt to tackle this issue on a case-by-case basis will struggle to keep up with each new piece of regulation and mounting requests by regulators and enforcement authorities and soon face the ire of shareholders and customers.

Boards should start from three fundamental questions:

What does ESG mean for us?

How do ESG and sustainability fit into company strategy, the interests of our stakeholders and the approaches of our competitors?

What policies, processes and data collection workflows do we need to credibly implement our ESG strategy?

Rather than simply playing catch-up with ESG regulation as new requirements come into effect, businesses should take a strategic approach. That means developing policies and processes that are not only compliant with law, but also relevant to their stakeholders, benchmarked against their peers and material to their activities.